Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

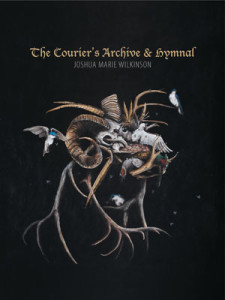

The Courier’s Archive & Hymnal, Sidebrow Books, 2014

Synopsis: A book of prose inspired by Bashō’s Narrow Road to the Deep Interior

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

Perhaps if the poet has an idea in advance of the writing that might organize the work formally or thematically. For me, it was a way to chart change over time through different forms. And they all failed and were altered within the composition anyhow. And that’s what I’m after, learning from why something no longer fits the impulse that sparked it, but now seems to need something new. Finding what that is is probably what writing’s about. Living, too.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

I don’t work in conscious messages or themes. I try to write through whatever obsesses me at the moment, and if that obsession sustains the work, then it fuels the endeavor. If not, then not. I just try to realize that before I get too far in. Usually, I don’t. More on which below.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

I think it means less and less; but I’m more bored by it than I am discomfited by it, probably.

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

I wrote the same number of sentences and lines as Bashō. And I attempted to include the same number of moons that he did in his book. That moon business was the only content-based constraint.

Did you allow yourself to break your own rules?

Yes, I found it impossible to note the moon with the frequency that Bashō does in his book.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

My book isn’t comprised of poems, but I hope that each line and each sentence can body forth alone just as it resonates and reshapes the whole, as well. In whatever way it fails, I hope it presents the good mess of experience rather than the pretense of the perfected.

At any point did you feel you were including (or were tempted to include) weaker poems in service of the project’s overall needs? This is a risk, and a common critique, of many project books. How did you deal with this?

I tend to slash a lot. I don’t think it’s for me to say what’s weaker and what’s stronger. I’m the least knowledgeable person about my own books, to some degree. I find the lines in this book still resonate with me. And my editors at Sidebrow were a terrific help with those kinds of decisions and questions.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

I always work on things simultaneously and let one book seep into another. Their voices intertwine and they ghost and thwart each other. And I like that a lot.

Did you ever lose momentum, bore yourself, or worry that your project could not be sustained for a full-length book? How did you push through?

I cut and cut and cut. I do that until the leaps are big and odd enough to surprise and bewilder me. Then sometimes I share it with friends and see how it feels and cut some more.

As you were writing, were you influenced by your experience or perception of how project books are received by readers and editors (either positively or negatively)? Do you feel differently about your book being defined as a “project book” now that it has been published than you did when you were writing it?

This had no noticeable impact on me. I assume that readers will resist or dislike my work to some degree and this, of course, frees me immensely to find out what I have to think and see and feel and want and say in the poems without trying to please or cater or ever predict. I write to my friends, to some extent, so if I can get into them then that’s good company, as far as I can see. If strangers like it, then I’m pleased of course.

Do you have a sense of whether the fact that this is a project book helped position it to find publication more easily? Has it helped you find readers?

I’m not sure about this. I wanted this book to stand on its own, but it also marks the awkward halfway point between two books on either side of it—since it’s the third in a five-book sequence I call the No Volta pentalogy. I think it’s decreased my readership significantly, but every book after your first book probably does. I’m kidding. But I suspect I’m not kidding too.

As a reader, are you drawn to project books? What project books have influenced you or have you enjoyed, and what do you think makes those books successful?

I’m less and less inclined toward project books. If something like Bhanu Kapil’s Humanimal or Tan Lin’s Insomnia and the Aunt fit the bill, then I’m down. But I find myself increasingly drawn to books of lone poems that rattle me: Cedar Sigo’s, Paul Killebrew’s, Elizabeth Willis’s, Emily Hunt’s, and many others lately. Then a new Cole Swensen book comes out, and she can use a single thing (a park, a calendar, ghosts) to write out a whole world. So it cuts all ways for me.

What effect do you think the prevalence of project books is having on poetry in general?

I think it will deaden it some extent. As more and more poets hunt for academic jobs to fill a niche, I think the project book is a proxy to say I’m working on something “important” and “unified” like a collection of essays or a novel. But really, I don’t give a shit about that. I just want a good poem to get into me—whether it’s four lines or four-hundred lines…Creeley, Oppen, Niedecker, H.D., Dickinson, and Celan are a few of my favorites—and I love their shortest discrete poems the best, so there’s that.

As a teacher, how do you see the prevalence of project books and other poetic constraints affecting your students’ writing?

Yeah, I teach grad students and I find that year after year they feel a bigger pressure to have a “project,” and I encourage them to discard that noise and just write what they want to write, line for line. Usually once they relax and give up on the big “project” they write better stuff anyways—because then they’re sensing and feeling and thinking and dredging with each phrase, rather than fitting it under some readymade, pre-planned umbrella that they’re already bored of.

Have you abandoned other project attempts? How did you know it was time to let go? What happens to project poems that never amass a full-length book?

Lots of abandoned ideas, half-starts, aborted missions. They get squelched in the flames, where they belong, whence they came.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

After I finished the No Volta pentalogy (Selenography, Swamp Isthmus, The Courier’s Archive & Hymnal, Meadow Slasher, and Shimoda’s Tavern), which took me about ten years or so, I wrote a book of little poems called The Easement on airplane flights across the country. They are about falling in love and making mistakes, and confusing those two. I wrote them quickly, by hand, each beginning with a line from Mandelstam. I guess it’s just another project, but I like them just fine. For now, anyways.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Don’t do it. Let yourself fail at it. Enjoy it. Cannibalize it for the scraps it might yield. Stay in it unless it starts to suck you down. If it’s fun and feels like you’re risking something, follow it. If it doesn’t, then fuck it. We don’t need any more “project” books any more than we need a bunch of vacuous lines to fit an “idea.” Never mind the idea if its constraint doesn’t free you to write something that moves you. Write a poem that makes you feel through language and gets you to say something you didn’t know you could put language to.