Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

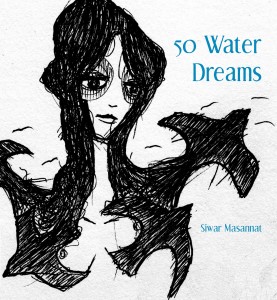

50 Water Dreams, Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2015

Synopsis: 50 Water Dreams follows the voices of personas in multiple, related spaces of tension and conflict.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

I suppose 50 Water Dreams is a project book because it follows and organizes itself around certain voices and themes. I generally understand a project book as one whose parts move formally and/or thematically in concert. Perhaps a project book’s individual parts exhibit a relation to each other that is more shaped or controlled by the poet than individual poems in a collection.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

After I wrote the first poem, I recognized that I wanted to explore how these voices and landscapes interact and perhaps “make” each other. As they started to take shape and move and interact in various directions, I allowed myself to follow them and see where they might go. I was interested in how power relationships emerge through language, and how language and production of knowledge are tools of exerting power. The voices organized themselves around my obsessions, a simultaneous sense of proximity to and distance from violence, and the gaps in my understanding of—and lack of reconciliation with—political rhetoric and metaphor. I had the metaphor of the colonized land as a raped woman in mind, and so I partially worked from it. Throughout the process I knew that I couldn’t completely unravel it or dislocate the implications within it, but that I needed to speak through some of these gaps.

As I worked on my thesis, the voices (re)emerged, developed, and changed. I tried out different forms and shapes of poems. The process was messy but was also guided by exploring and tuning the directions these voices took. I suppose I was also preoccupied with the notion of personas both fitting into and eluding real-life contexts. I was writing through my sense of being positioned inside and outside different languages, spaces, and contexts. I wanted the voices to gesture towards the real and imagined, in an attempt to recognize the limits of capturing my resistance to the rhetoric of occupation and my discomfort with the metaphor.

Did you allow yourself to break your own rules?

For the most part, I enjoy the generative aspect of rules and constraints as long as I can reconsider and adjust them after drafting. I had to break some of my rules in order to generate new poems. As I revised, I altered some of these rules, or created new ones. The drama-like sections of the book, for instance, required some reshaping, so I had to create a sense of consistent form, yet also let each poem be itself. The process was messy but was also guided by exploring and tuning the directions these voices took. The generous feedback I received from my friends, classmates, and professors was extremely helpful for my process of discovery and revision.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

I tried writing the book as a sequence, or as one long poem, but found that I had to work towards a middle ground that allowed for the variety in how the poems functioned. At some point in the process I had to strike a balance between how related the poems wanted to be and the poem as a self-contained entity. Some of the poems stood on their own, whereas others were more dependent on the context of the project. There are a lot of drafts that didn’t make it, and revision turned towards making some of the work more intelligible as a whole. Thinking of language accessibility was also an issue, perhaps because I was simultaneously thinking in and borrowing from Arabic and English. So, I found that I needed to work with and against my natural inclination to mess with syntax and grammar towards achieving more clarity and preciseness in expression.

Though I didn’t think of the project as a narrative, many of my readers encountered it in that way. I believe I am still discovering the various ways in which narrative functions. But at the time of writing this project I did not have a particular end in mind, but considered the project to be perhaps more disjointed and multivocal. So, it was challenging to consider how to make an arc of connections work effectively without rendering the project either as a coherent narrative moving towards one end or alternatively letting it become too disjointed. A lot of the revision process revolved around finding ways to make the poems build on, connect, and flow into each other.

As a reader, are you drawn to project books? What project books have influenced you or have you enjoyed, and what do you think makes those books successful?

I enjoy both non-project and project books. I also enjoy books that incorporate a number of poem sequences or series within them, such as Matthea Harvey’s mermaid poems in If the Tabloids Are True What Are You?. I find it delightfully fresh and surprising how the whimsy and preciseness of image works with or for narrative tension in her work. I also enjoyed reading Dawn Lundy Martin’s Discipline very much and think it is one of these books I would want to reread over and over. For me as a reader, I feel that I encounter a simultaneous cyclicality and sense of timelessness in the book, which temporally positions individual episodes of aggression within a context of systemic violence with great acuity and nuance. I suppose I enjoy sequences or series of prose poems a lot—both of these books employ the form!

Have you abandoned other project attempts? How did you know it was time to let go? What happens to project poems that never amass a full-length book?

I really enjoy writing through voices and personas, but there have been projects that I abandoned or kept on hold because I lost touch with the voice or organizing theme of the project. Sometimes, I return to drafts and don’t see potential in them. Other times, I feel I am not yet ready to undertake a particular theme or form, or that the voice I have been writing through needs more time to percolate.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

I wrote a bunch of new individual poems after the first draft of the book was done. I had the opportunity to attend a Vermont Studio Center (VSC) residency the summer after I graduated, which wouldn’t have been possible without the generous support I received from George Mason University and VSC. That time was productive and quite lovely. I enjoyed the sense of freedom in writing poems that did not have to “fit” a project.

At the moment, I am working on separate, but related, sequences that will probably be part of my dissertation. One of the sequences is an elegy that I have been working on for a while now. I have never written an elegy before, so this particular work feels like a process of discovery that is strangely painful and compelling.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

As a student, I feel that finding the balance between letting poems develop organically and following a guiding principle is important. This balance is not only good for allowing the poems to find shape and meaning beyond the poet’s control, but also to alleviate some of the uncertainty that emerges in the writing process. I find that reading, in a variety of genres and topics, is also helpful for sustaining productivity. For me, reading is often what motivates me to write and helps me reconsider what my own work is attempting to do.

I also made it a habit to revise when I felt that I wasn’t able to generate new poems, which helped me stay productive. Moving back and forth between different processes of revision was also very helpful for me—when I found it difficult to revise individual poems, I would revise whole sections instead. So, breaking up the process and switching it can help disturb the feeling of monotony that might accompany working on a single project.