Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

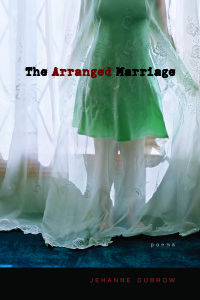

The Arranged Marriage, University of New Mexico Press, 2015

Synopsis: A book-length sequence of prose poems about a mother’s experiences with different kinds of forced intimacy and closeness.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

The Arranged Marriage is a project book because its poems emerged out of a shared process and subject matter; I spent two years interviewing my mother, focusing on three different stories: an exiled, Jewish childhood in Latin America; an incident of extreme emotional and physical violence; and an arranged marriage in the aftermath of that violence. The collection is also unified by form. I use narrow prose poems that resemble newspaper columns and that employ a detached voice, an attempt at reportage to speak about trauma and violence.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

The stories in The Arranged Marriage are narratives my mother has told me since I was a very little girl. I think I was always meant to write this collection. These stories are part of my identity, my way of understanding the threatening world. But, I usually work in received and fixed forms. So, it took learning how to write my version of a prose poem in order to draft The Arranged Marriage. I can’t imagine having written these poems as sonnets or as elegant lines of blank verse. They are cold and violent and need to resist the aestheticizing impulses of traditional form.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

Yes. I love the term. For me, project means purpose. It’s not prescriptive. Perhaps, because I love the boundaries and constraints of fixed forms, a project book seems to pose the same liberating challenge as does a sonnet or a villanelle. A project book is simply a bigger container—not 14 lines but 40 to 80 pages.

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

I was always very clear about the book’s scope and the fact that I would write about these three distinct but interconnected moments from my mother’s life. For the first year that I worked on the project, I thought the book would be structured chronologically and in three parts. The discovery that I needed to braid the stories together came very slowly, as I began to think more deeply about trauma as a shattering, a breaking of the glass of narrative. Getting that braid right took at least another year, during which time I also realized that the collection should have no sections, so that it would be more immersive for the reader, breakneck, suspenseful.

At any point did you feel you were including (or were tempted to include) weaker poems in service of the project’s overall needs? This is a risk, and a common critique, of many project books. How did you deal with this?

This is always a worry when working on a project book; the burden of narrative and linearity can cause one to keep a weaker poem for the purpose of storytelling. With The Arranged Marriage, I had to embrace the gaps, to accept the fact that this is a collection both about trauma and mimetic of trauma. Once I came to recognize the value of fragmentation, I was able to toss weaker poems that were only serving a narrative purpose.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

Because I always write poetry collections that could be called project books, I’m very aware of the danger of boring myself or of losing momentum. So, I always work on 2 to 3 manuscripts at a time, sliding back and forth between projects, in order to ensure that I remain engaged and surprised by own writing.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

Working on several books simultaneously makes ending one project easier. By the time I finished The Arranged Marriage, I was already deep into two other poetry collections, Dots & Dashes and Dinner with Kathleen Battle (both of which are most definitely project books), a collection of “meditative close readings” of the poems of Philip Larkin, and a book-length essay about perfume tentatively titled fromsmoke.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

If you’re going to write a project book, you better dearly love your project. There used to be a sign above my computer: NO BLOODLESS POETRY. Your project can’t be bloodless. You must be willing to dream it when you sleep, to find threads or echoes of your project in everything you read or see or discuss. You must be willing to ruin dinner conversations with your obsession. This project should be the guest who comes to stay and will not leave.